Canada Reconsiders Its Trade Alignment as China Offers a Way Out of Tariff Crossfire

OTTAWA — What began as a quiet trade dispute has evolved into one of the most consequential economic recalibrations Canada has faced in decades. After months of tariff pressure from Washington and an unexpected diplomatic overture from Beijing, Canadian officials are weighing whether their long-standing alignment with the United States can continue to anchor the country’s economic future.

The shift began subtly. As the United States tightened tariffs on steel, aluminum and most recently automobiles, Canadian policymakers were caught between loyalty to their largest trading partner and the rising economic costs of that loyalty. The tensions escalated in early October when Howard Lutnik, the U.S. commerce secretary, delivered a blunt warning in Toronto: “When it comes to vehicle production, it will be America first, Canada second.”

The threat of a 25 percent tariff on Canadian-made vehicles — a sector employing nearly half a million people — sent shock waves through Ontario’s manufacturing belt. Economists in Ottawa estimated that billions of dollars in auto exports were suddenly at risk. American economists, too, warned that U.S. automakers would face higher costs and slimmer margins. Yet the Trump administration did not retreat.

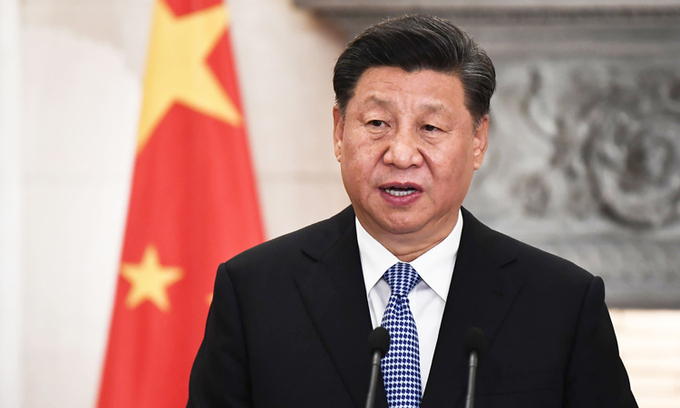

Against this backdrop, Beijing saw an opening. China quietly communicated that it was willing to eliminate its retaliatory 100 percent tariffs on Canadian canola if Ottawa lifted its own 100 percent duties on Chinese-made electric vehicles. It was a transactional offer, but one that appealed to several Canadian constituencies: farmers seeking restored access to a billion-person market, consumers looking for lower-cost EVs, and climate officials aiming to expand clean-energy adoption.

For decades, the idea that Canada might meaningfully diverge from U.S. trade policy was political heresy. Yet the tariff conflict has exposed the vulnerability inherent in that dependency. Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government now speaks openly about “sectoral resilience,” a strategy that shifts Canada away from sweeping, single-partner agreements toward smaller, diversified partnerships.

In mid-October, Ottawa rolled out new measures to support domestic manufacturing and energy sectors while maintaining a 25 percent tariff on U.S.-made vehicles — a signal that Canada would no longer follow Washington automatically. At the same time, officials lifted several retaliatory duties to encourage dialogue with global partners, including China.

Industry analysts say the new approach reflects pragmatism rather than geopolitics. China is not replacing the United States; instead, Canada is seeking leverage it has long lacked. Export volumes to Asia are already rising, and talks with Beijing on clean-energy cooperation and critical minerals have accelerated.

The ripple effect extends beyond North America. In Japan and South Korea — two of Washington’s most dependable allies — frustration with U.S. tariff demands has become increasingly public. Tokyo has refused to finalize a trade agreement without broader concessions. Seoul has pushed back even harder, particularly after U.S. immigration authorities detained Korean technical workers during a raid at a Hyundai site in Georgia, sparking outrage.

For Canada, the dilemma is less dramatic but no less urgent. The United States remains its closest economic partner, yet the assumption of unconditional alignment — a cornerstone of postwar policy — has begun to erode.

“Trade relationships built on pressure are inherently unstable,” one senior Canadian official said. “We’re not choosing sides. We’re choosing options.”

As Canada navigates between two global powers, its decisions in the coming months may redefine not only its economic strategy but its geopolitical identity for years to come.